Questions? Need help placing your order?

Email us at support@wordonfire.org or call 866-928-1237.

CUSTOM JAVASCRIPT / HTML

About the Collection

The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), a gathering of Catholic bishops from around the world, was one of the most significant cultural and ecclesiastical events of the twentieth century. Though practically everyone acknowledges its importance, Catholics have been debating its precise meaning and application for the past sixty years. On the one hand are “radical traditionalists” who claim that Vatican II betrayed authentic Catholicism and produced disastrous consequences in the life of the Church; on the other, “progressives” who saw the council documents as a first step toward more substantial changes in the Church.

But even as many voices have argued about the council since the documents appeared in the mid-1960s, the documents of Vatican II are still widely unread, and if they are read, often misunderstood. This groundbreaking collection from Word on Fire is designed to address that problem.

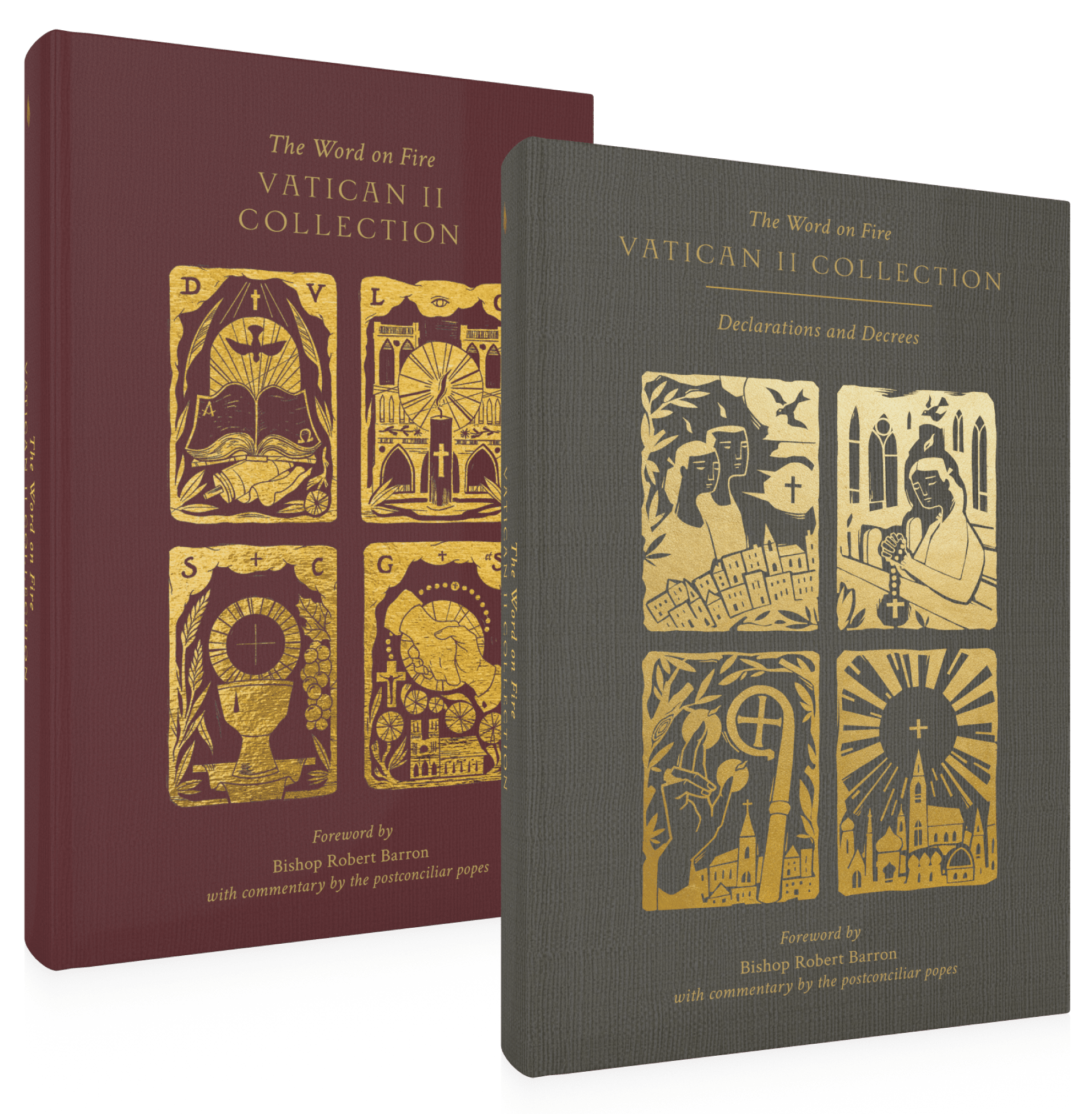

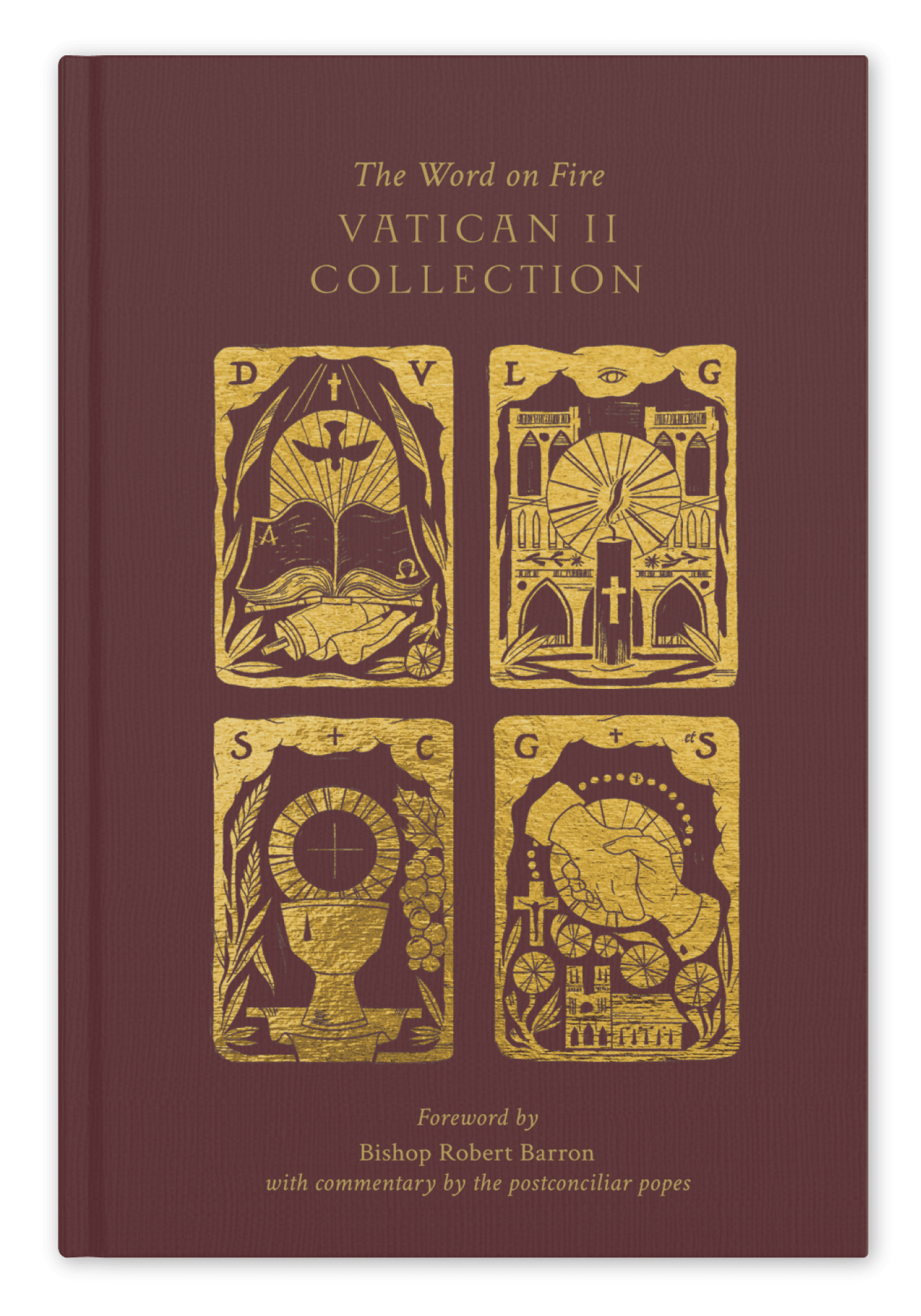

Volume I: Constitutions

Word on Fire Institute | March 8th, 2021

Hardcover | 392 Pages | 6" x 9"

The first volume of The Word on Fire Vatican II Collection features the four central documents that most fully articulate the vision of the council—Dei Verbum, Lumen Gentium, Sacrosanctum Concilium, and Gaudium et Spes—with illuminating commentary from the postconciliar popes and Bishop Robert Barron interspersed throughout, along with beautifully carved linocut art.

The collection also includes the opening address of Pope St. John XXIII, the closing address of Pope St. Paul VI, a foreword from Bishop Barron, an afterword from theologian Matthew Levering, and helpful appendices listing key terms and figures and answering frequently asked questions.

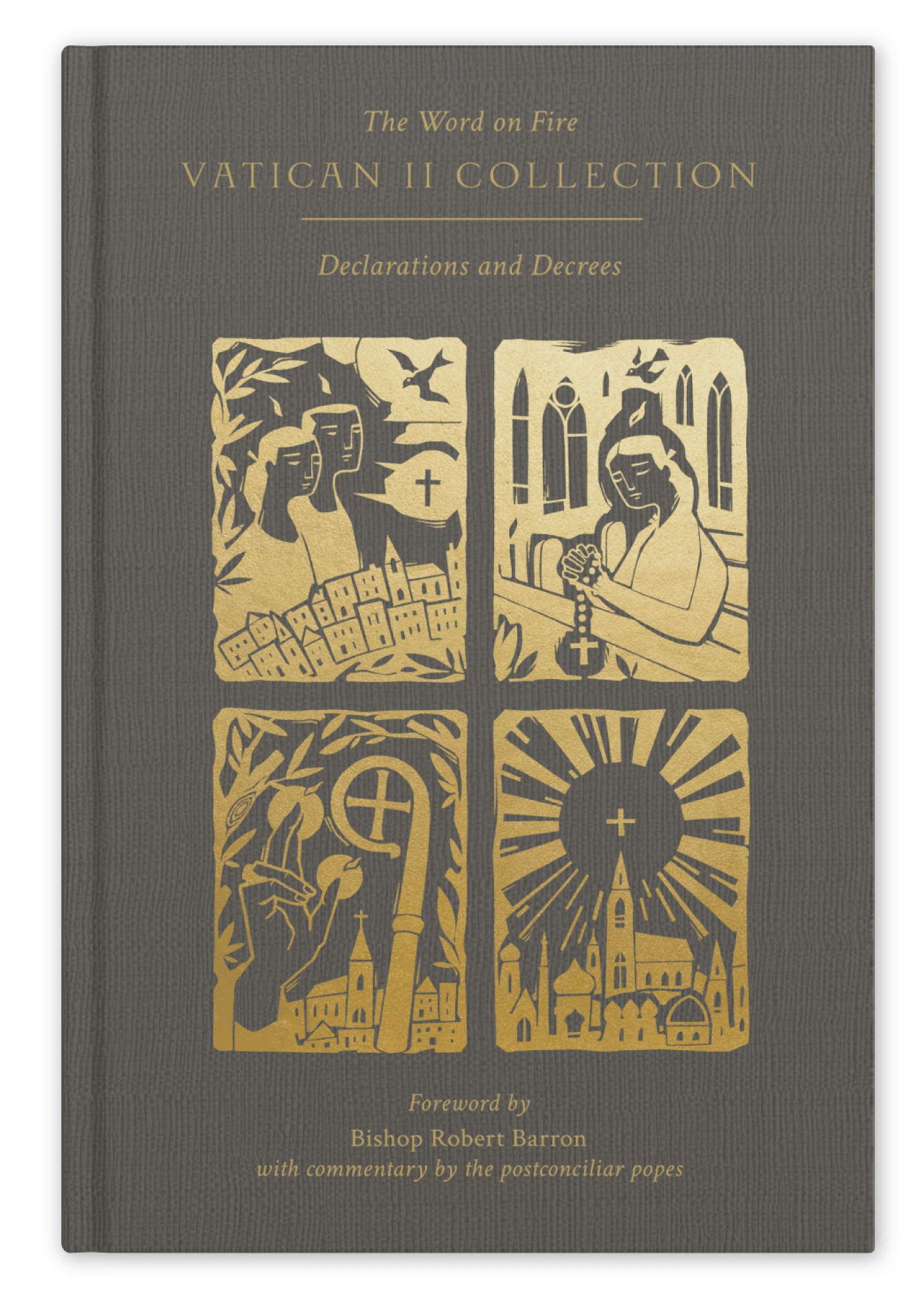

Volume II: Declarations and Decrees

Word on Fire Institute | February 13th, 2023

Hardcover | 504 Pages | 6" x 9"

This second elegant, hardcover volume contains the twelve declarations and decrees issued by the council, rounding out its entire corpus of documents. In these pages, you will discover the Church’s teaching on education, religious freedom, evangelization, and more. While shorter and lesser-known than the four major constitutions, these additional texts are nevertheless essential to communicating the very heart of Vatican II.

Like the first volume, Declarations and Decrees features commentary from the postconciliar popes and Bishop Robert Barron to help readers understand how the Church authoritatively interprets different passages. It also includes a foreword by Bishop Barron, an afterword by theologian Matthew Levering, and helpful appendices listing key terms, figures, and answers to frequently asked questions.

The Word on Fire Vatican II Collection is a robust but readable journey into the true history and purpose of the Second Vatican Council, and a compelling call for an enthusiastic return to its texts today.

Six Unique Features Of This Beautiful Collection

1. A foreword from Bishop Robert Barron and an afterword from theologian Matthew Levering

2. The four central documents of Vatican II (Dei Verbum, Lumen Gentium, Sacrosanctum Concilium, and Gaudium et Spes)

3. The twelve declarations and decrees issued by the council

4. Commentary from Pope St. Paul VI, Pope St. John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI, and Pope Francis, as well as Bishop Robert Barron

5. Original linocut art, carved and hand-pressed on an antique cast iron book press, by Cory Mendenhall

6. A helpful appendix answering frequently asked questions about the council, including: What is Vatican II? Was Vatican II merely a “pastoral” council? And are Catholics free to ignore, disparage, or reject Vatican II?

“With the passing of the years, the Council documents have lost nothing of their value or brilliance. They need to be read correctly, to be widely known and taken to heart as important and normative texts of the Magisterium, within the Church’s Tradition.”

— POPE ST. JOHN PAUL II

Some Catholics in America today are increasingly vocal in their attacks on the Second Vatican Council itself—an ecumenical council of the Church summoned and presided over by the successor of Peter. How should we understand this disturbing trend?

In this video, Bishop Robert Barron traces the missionary purpose of Vatican II from the conciliar texts themselves, through the New Evangelization, and finally to the Magisterium of Pope Francis, whose influences situate him in a particular camp in this history.

“The Second Vatican Council Documents, to which we must return, freeing them from a mass of publications which instead of making them known have often concealed them, are a compass in our time too that permits the Barque of the Church to put out into the deep in the midst of storms or on calm and peaceful waves, to sail safely and to reach her destination.”

— POPE BENEDICT XVI

Understanding the Post-Vatican II Church

In this episode of the Word on Fire Show, Bishop Barron and Brandon Vogt talk about how to make sense of all the names, groups, and movements surrounding the Second Vatican Council. What are the key things to know, and how have they shaped today’s Catholic Church?

CUSTOM JAVASCRIPT / HTML

CUSTOM JAVASCRIPT / HTML